How do accumulating ETFs benefit individual investors exactly? Net asset value, authorized participants and creation/redemption mechanisms

Even a superficial read about Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) will reveal that there are two strategies by which ETFs handle dividends. Either they are passed to the individual ETF investors by the so-called distributing ETFs, or the fund keeps the dividends and promises to reinvest them into the market in what are called accumulating ETFs. You may now wonder, as an accumulating ETF investor, what tangible benefits do you get from this strategy?

The immediately obvious advantage of having the fund reinvest your dividends for you is that, well, you don’t forget to do it. The major reason to do this, however, is that your dividends are not taxed because, well, you never received them in the first place. For this reason, investing in accumulating ETFs will provide higher long term returns after taxes and fees.

However, as an investor in accumulating ETFs you may be puzzled to realize that the number of shares you own never goes up unless you yourself purchase some. Aren’t accumulating ETFs supposed to reinvest dividends? Somewhat naively, I thought that an accumulating ETF would give me dividends as additional shares rather than cash, but it doesn’t! So how do I benefit from dividends, how do I see that they exist? I dived into a moderately deep rabbit hole to understand why, and here I summarize what I found (jump to the conclusion at the end if you are impatient).

Net asset value (NAV)

To understand where dividends go, you need to know about the net asset value (NAV) of an ETF. Simply stated, the NAV is the net value of the fund, assets minus liabilities, divided by the number of shares. Imagine an ETF owning 80 shares of Company A and 20 shares of Company B. These shares are part of the fund’s assets, and if they are currently traded at 20 for Company A and 40 for Company B, then the fund owns 80x20+20x40=2400 in assets. Assuming for simplicity that the fund owns no cash (the other major type of asset) and has no liabilities, then its net value is also 2400, and if there are in total 100 circulating shares of this ETF then its NAV is 24.

Dividends increase the NAV of accumulating ETFs

Imagine that today is dividends day and that the accumulating ETF above receives 0.5 per share from Company A and 1 from Company B. Then, the ETF receives in total 80x0.5+20*1=60 in cash. Because of this additional cash, the assets of the funds increased from 2400 to 2460, and its NAV is now 24.6. Alice, owning 10 shares of this accumulating ETF, would still own 10 shares after dividends are issued by the two companies, and will not receive a single penny.

Dividends do not increase the NAV of distributing ETFs

While an accumulating ETF would keep that cash and increase its NAV, a distributing ETF would pass the cash to investors. As the ETF received 60 in dividends and is split into 100 shares, investors would receive 60/100=0.6 per share in dividends. Therefore Bob, owning 10 shares of the distributing ETF, would receive 6 in dividends.

Ah cool, the NAV increases. So?!

To recap, after dividends from accumulating and distributing ETFs are handled, Alice owns 10 shares with a NAV of 24.6, and Bob owns 10 shares with a NAV of 24 plus 6 in cash. Somehow it feels balanced, because both Alice and Bob own assets worth 246: for Alice 24.6x10=246 and for Bob 24x10+6=246. However, if you are Alice, you may feel something is missing: you received nothing from the accumulating ETF! The market price at which the ETF shares are traded is determined only by the laws of demand and offer and has nothing to do with the NAV, so Alice does not feel richer at all: even if the NAV of her fund increased, the market price did no.

Authorized participants (AP) pin market price to NAV

As described, the situation does look rather inconvenient, as the market price of an ETF is free to fluctuate according to market demand. But wait, if this is actually the case, how can ETFs track an index without straying, if they are also bought and sold like any other security? This is why authorized participants (AP) exist. APs are large financial institutions with lots of cash that sit between an ETF and the market and ensure that the market price does not deviate from the NAV by using two mechanisms called Creation and Redemption. Why do they do this? Because they make money in the process!

Creation and Redemption allow APs to control the market price

Creation and Redemption are two mechanism that respectively increase and decrease the number of available ETF shares. They allow controlling the market price of an ETF by modifying the supply side of the equation: creating shares increases supply and reduces the price, while redeeming shares reduces supply and increases the price. Conceptually, an ETF share is nothing more than a piece of paper which says “this paper is worth one share”, so in principle the owner of the ETF can create as many shares as they want. But obviously they just can’t create shares at will and distribute them around, because this will only devalue the existing shares without achieving anything more than angering investors.

Instead, shares are created by the fund selling them to an AP at the NAV price. This is extremely important: APs can purchase ETF shares at the NAV price! The NAV price!! NAV!!! The NAV is regularly reported publicly by the fund. So if you are a cash-strapped AP and notice that the market price of an ETF is higher than its NAV, what do you do? Obviously, you purchase ETF shares from the fund at the (lower) NAV price and sell them to the broader market for the (higher) market price, pocketing the difference! This is the creation mechanism in a nutshell. Redemption works in the opposite direction: if the market price is lower than the NAV, for example just after the fund receives dividends, APs purchase shares from the stock exchange and sell them to the fund at NAV price for profit. In our example above, the NAV increased to 24.6 after dividends while the market price remained at 24 (because APs matched it to the NAV before dividends), therefore an AP could purchase an ETF share in the stock market for 24 and redeem it with the fund for 24.6, with a profit of 2.5%.

I did not mention an important detail, namely that creating and redeeming shares is not performed with cash but rather with the underlying securities that make up the index tracked by the ETF. In our example, Company A was trading at 20 and Company B at 40. Following the 80/20 allocation above, the AP can exchange with the fund one ETF share, purchased for 24 in the stock market and redeemed for 24.6 with the fund, and receive (24.6x0.8)/20=0.984 shares of Company A and (24.6x0.2)/40=0.123 shares of Company B. At this point the AP could sell these shares in the stock market for 20x0.984+40x0.123=24.6 in cash, thus realizing the same gain of 2.5% or simply keep those shares and use them in the future to create ETF shares when the market price is higher than the NAV. There are several other reasons why ETFs benefit from APs, including lower ETF fees; read more here.

But then the market price of accumulating ETFs should be higher than that of its distributing siblings!

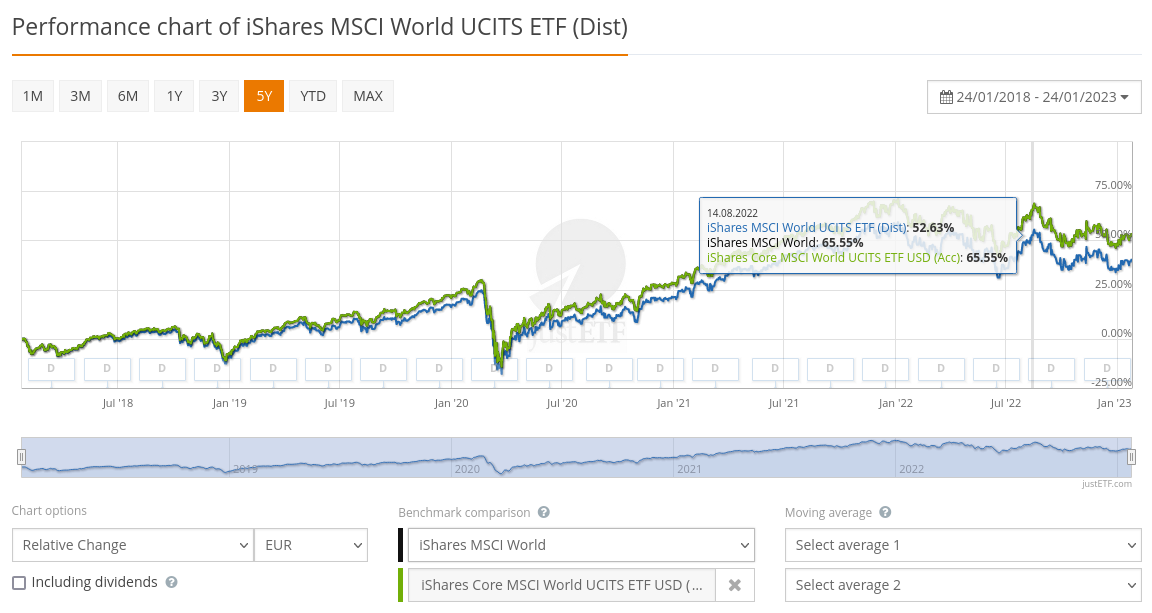

Right!? Because the NAV of accumulating ETFs keeps increasing while that of distributing ETFS does not, and APs will match the market price to the NAV. And indeed accumulating ETFs are pricier! Had I bothered to check before starting to read about NAV and APs I would have saved one afternoon (but I’d be slightly more ignorant). This is the relative change in market price during the last five years of an accumulating ETF, in green, and a distributing ETF, in blue, both tracking the MSCI World index:

As you can see, on August 14th, 2022 the market price of the accumulating ETF increased by 65.55% compared to January 1st, 2018, while in the same period the distributing ETF only increased by 52.63%. You can also see, at the bottom left, that dividends are not reinvested in the distributing ETF. Not including dividends gives the historical market price, while including them gives the return of an investor. By reinvesting dividends, the total (pre-tax, without fees) returns of investors in accumulating and distributing ETFs are identical: accumulating ETFs investors will own fewer but pricier shares, while distributing ETFs investors will own more, cheaper, shares, and this balances out so that the total assets are worth exactly the same.

Conclusion

The question I started with was: “where do my dividends go when investing in accumulating ETFs, and how do I benefit from them?” I was wondering this because of a misconception that led me to think that dividends would reach me as additional shares rather than cash. Instead, as an investor in accumulating ETFs I benefit by higher market prices compared to the equivalent distributing ETF, but the total value of the assets I own is the same.