Joint epitope selection and spacer design for string-of-beads vaccines

We have just submitted a paper describing a new framework for vaccine design. Similarly to our previous project, the main innovation here is that we take a holistic approach to the design problem, and show how this improves the end result.

Let me start by quoting the abstract:

Motivation: Conceptually, epitope-based vaccine design poses two distinct problems: (1) selecting the best epitopes eliciting the strongest possible immune response, and (2) arranging and linking the selected epitopes through short spacer sequences to string-of-beads vaccines so as to increase the recovery likelihood of each epitope during antigen processing. Current state-of-the-art approaches solve this design problem sequentially. Consequently, such approaches are unable to capture the inter-dependencies between the two design steps, usually emphasizing theoretical immunogenicity over correct vaccine processing and resulting in vaccines with less effective immunogencity.

Results: In this work, we present a computational approach based on linear programming that solves both design steps simultaneously, allowing to weigh the selection of a set of epitopes that have great immunogenic potential against their assembly into a string-of-beads construct that provides a high chance of recovery. We conducted Monte-Carlo cleavage simulations to show that, indeed, a fixed set of epitopes often cannot be assembled adequately, whereas selecting epitopes to accommodate proper cleavage requirements substantially improves their recovery probability and thus the effective immunogenicity, pathogen, and population coverage of the resulting vaccines by at least two fold.

In one sentence, we propose a new approach that solves the two problems of vaccine design, selection and assembly, at the same time, resulting in more effective vaccines.

You can find the paper on biorxiv, and the software implementation on GitHub.

Update: this article was finally published in Oxford Bioinformatics!

Emilio Dorigatti, Benjamin Schubert, Joint epitope selection and spacer design for string-of-beads vaccines, Bioinformatics, Volume 36, Issue Supplement_2, December 2020, Pages i643–i650, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa790

Background

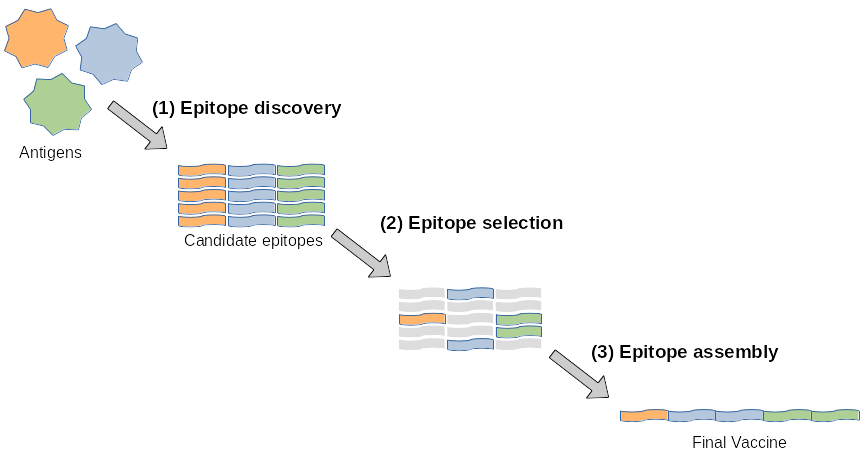

Designing a vaccine requires at least three steps: discovering all the epitopes from the target antigens, choosing which ones to put in the vaccine, and finding a good way to assemble them in the actual vaccine.

To clarify the terminology, antigens are the bad guys, agents that cause trouble, i.e. disease, for example viruses and bacteria. The type of vaccines that we focus on in this work is just a sequence of epitopes.

Epitopes are small pieces of these antigens that are recognized by the body as a source of trouble. To put it simply, once the vaccine is injected into the body it is picked up by normal cells, which start cloning it. Cells are continuously copying genes found in the DNA to create proteins that are necessary for their activities. This machinery is also exploited by viruses to proliferate, by the way.

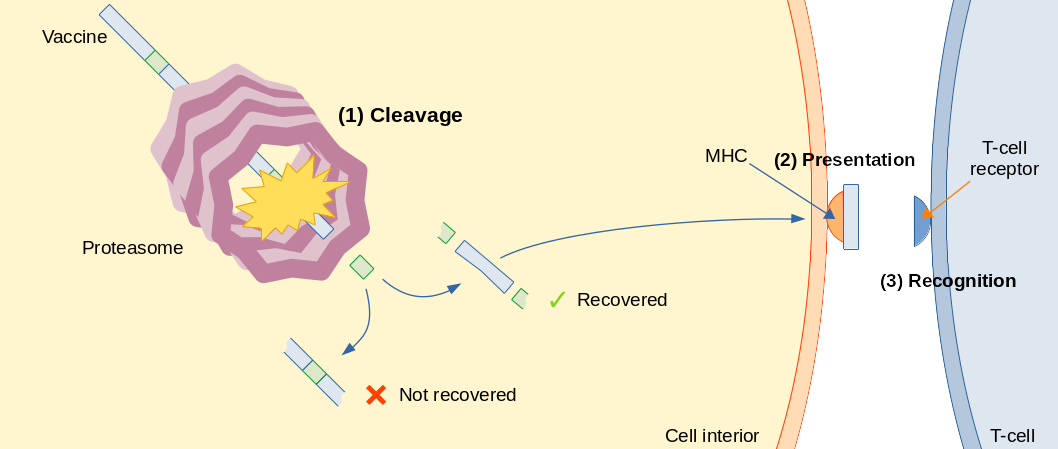

Some copies of the vaccine are then eaten by this cylindrical machine, called proteasome, that cut the vaccine sequence in certain positions. This is also a normal activity performed by cells in order to recycle old, malfunctioning proteins. Some of the protein pieces produced by the proteasome are loaded onto another protein, called MHC, and this complex of epitope-MHC is exposed outside of the cell, waiting for a T cell to pass by. T cells are like policemen that constantly patrol the body, and inspect the protein pieces shown by the MHC through a receptor on their surface. If this receptor binds to the epitope-MHC complex, the T cell knows something is wrong, and proceeds to alert the whole immune system, as well as to kill the cell showing the epitope.

We want to design vaccines that trigger this sequence of events. Therefore, we need to make sure that the epitopes we put in the vaccine can be properly recovered by the proteasome, instead of being cut in the middle. We also need to choose epitopes that can be presented successfully by the MHC, and recognized easily by T cells. All these steps have been studied individually but, and this is the main point of this paper, you need to consider all of them together to design effective vaccines.

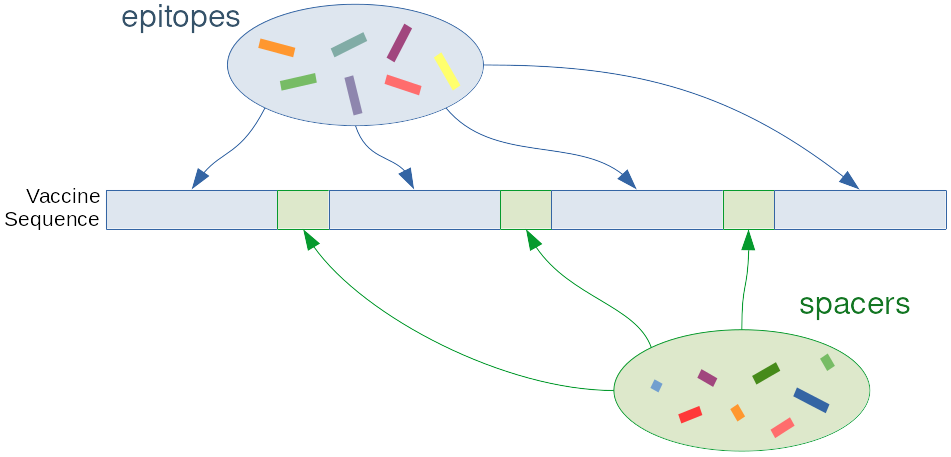

Here we focus on so-called string-of-beads vaccines, which are structured as follows:

In other words, we alternate epitopes and spacers Spacers are short, arbitrary sequences that we design to trick the proteasome into cutting the vaccine between them and the epitopes. If this happens, then the epitope is recovered and can (possibly) be picked up by the MHC. If the epitope is not properly recovered, e.g. because it is cut in the middle or not separated by its spacers, it is very unlikely that the MHC will recognize it.

Our contribution

The current state of the art is fragmented into tools that focus on proper selection of epitopes based on several criteria, and tools that focus on assembling a given set of epitopes into the vaccine. In this paper we propose a method that performs these two steps at the same time, and we show that this results in vaccines that are more effective.

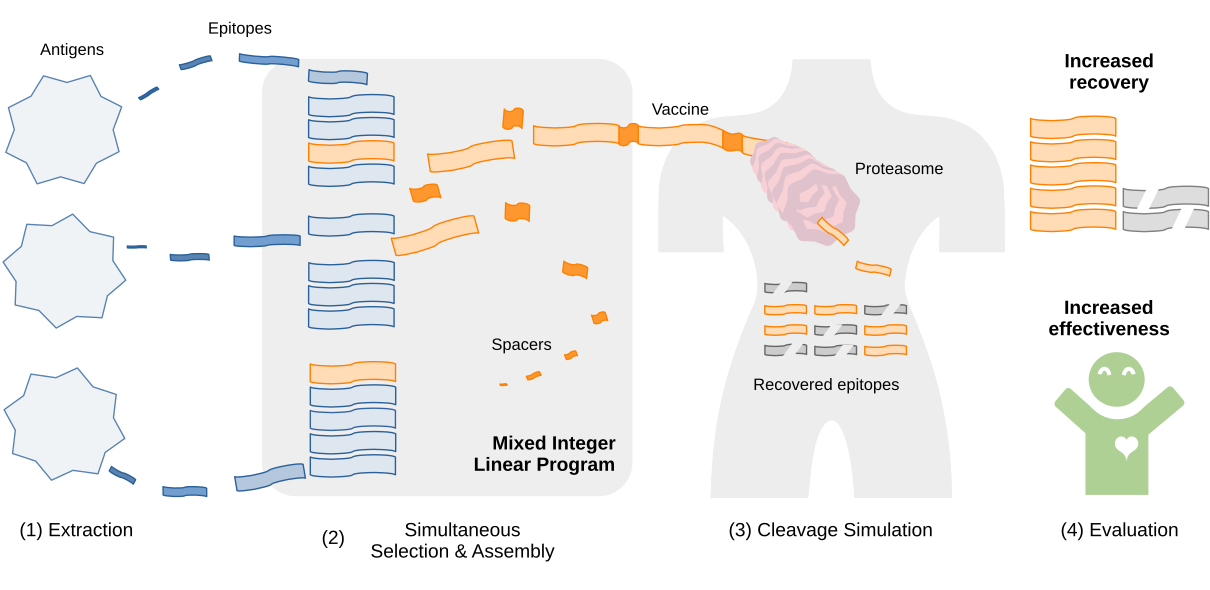

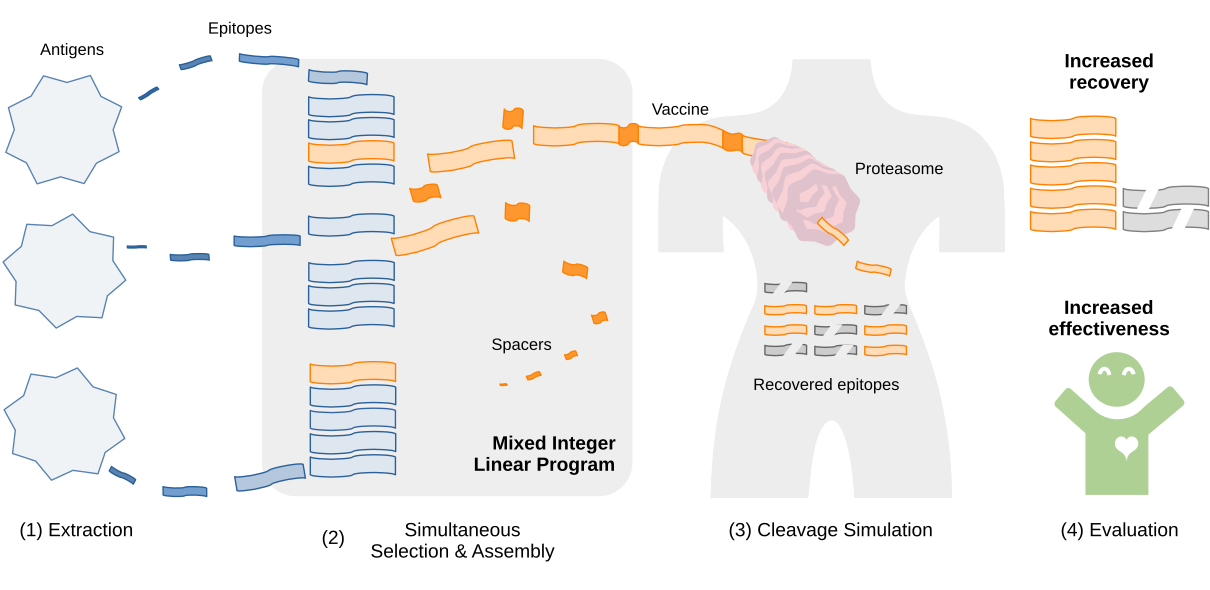

The picture above shows the four steps of our vaccine design framework. First, extract epitopes from the antigens of interest. Then, optimize the vaccine formulation using the linear program we developed. Finally, evaluate the vaccines by simulating the cleavage process.

Effective immunogenicity

We used a stochastic model of proteasomal cleavage to estimate the probability that each epitope would be recovered, and computed the expected immunogenicity of the vaccine as the average of the immunogenicities of each epitope, weighted by its recovery probability. The immunogenicity of an epitope measures, informally, how strongly the immune system responds to this epitope. In practice, we quantify this through the strength of the bond between this epitope and the MHC molecule, which can be predicted fairly accurately and is somewhat correlated with binding to T cells.1

The cleavage probability for each position in the sequence is estimated through a simple linear model2 that assigns a weight to each of the four preceding and the following amino acid. This probability is conditioned on the four preceding amino acids, which is why we assume that cleavage must happen at least four positions apart. You can think of the cleavage process as a fourth-order Markov chain, as cleavage in one position depends on cleavage not happening in the previous four positions. We could compute analytically the unconditioned cleavage probabilities, but most likely the formulas will not be computable in a linear program, therefore we only deal with the conditioned probabilities. Once a solution is found, we use Monte Carlo simulations to estimate these probabilities and compute the effective immunogenicity.

Linear program

We solve this vaccine design problem through mixed integer linear programming (MILP). A MILP is an optimization problem of this form:

\[\begin{align} \text{Maximize:} & \quad \textbf{c}^\intercal\textbf{x} \\ \text{Subject to:} & \quad \textbf{A}^\intercal\textbf{x}=\textbf{b} \end{align}\]Where $\textbf{A}$, $\textbf{b}$ and $\textbf{c}$ are coefficients that encode the problem at hand, in our case vaccine design, and $\textbf{x}$ is a vector of unknown variables. Some of these variables are constrained to be integers, and this restriction makes finding a solution much more complicated. There is a very developed theory behind solving such problems, and we use an off-the-shelf solver.

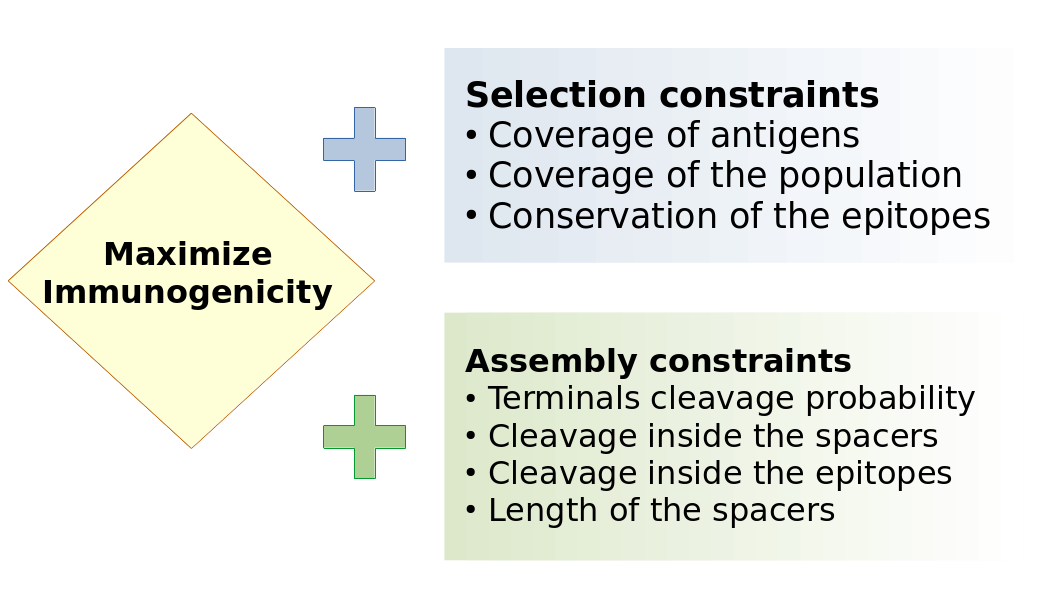

Our main contribution is therefore a MILP formulation to design vaccines. It can be divided in three parts:

There is a core program that select epitopes so as to maximizes the immunogenicity. On top of this core, we can add two blocks of constraints. The first block forces the vaccine to cover a reasonable amount of antigens, and to be easily recognized by most of the people that will be treated with this vaccine. The MHC proteins are highly variable among people, so that a vaccine designed for Asian people might not be as effective for the European population. Of course we can design a vaccine that works for both, but this could reduce the immunogenicity and make the vaccine less effective for everybody. The second block of constraints is concerned with enforcing high cleavage probabilities at the terminals of the epitopes, i.e. between them and the spacers, and low cleavage probabilities inside the epitopes themselves.

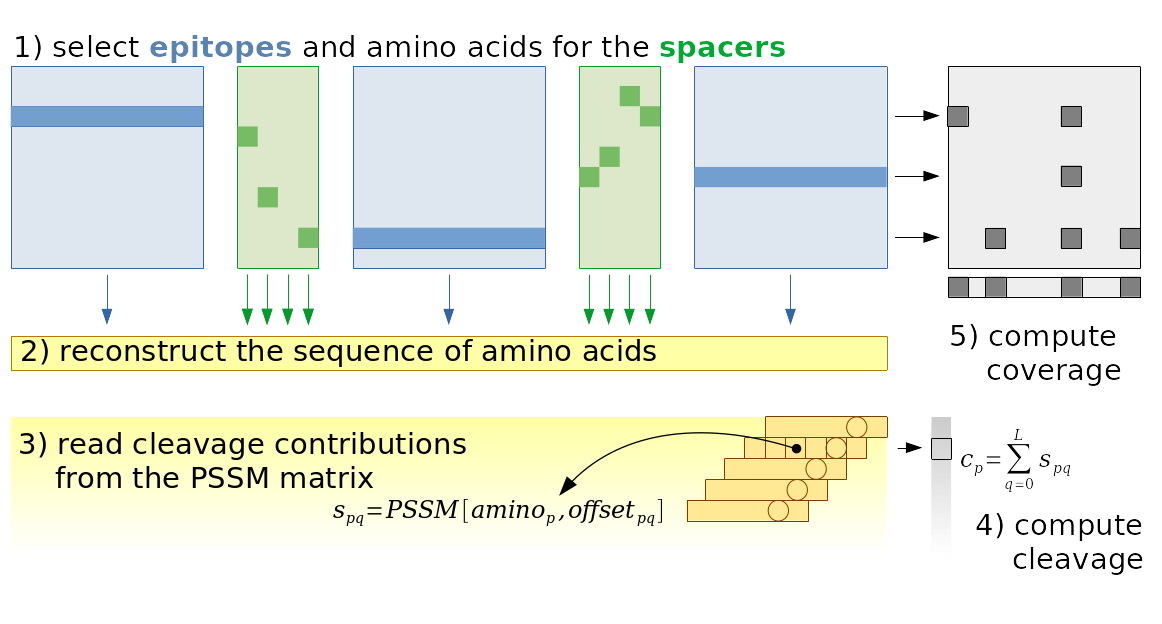

The linear program itself is fairly elaborate, most of the complexity being in the computation of the cleavage probabilities. A detailed discussion of the MILP (which can be seen in the supplementary material) is not in the scope of this blog post, but, conceptually, its core block is composed of the following steps:

There is one binary variable for each epitope/position combination, and one variable for each amino acid/spacer/position in the spacer combination. Based on the values of these variables, we can easily reconstruct the amino acid sequence of the vaccine. The third step consists in finding the coefficients for the linear model used to compute the cleavage score. This is not trivial, because the spacers do not have a fixed length. This means that some positions in the spacers are empty, therefore we have to compute the offsets dynamically. And since the offsets are dynamic, we must also read the coefficient matrix dynamically. This is not trivial (but not too complicated either), and is explained in detail in the paper. Once the cleavage probabilities are computed, it is trivial to constrain them to be larger or smaller than certain thresholds. Furthermore, from the selected epitopes we can find which antigens and types of MHC are covered by the vaccine, and from this it is again trivial to enforce certain levels of coverage.

Results

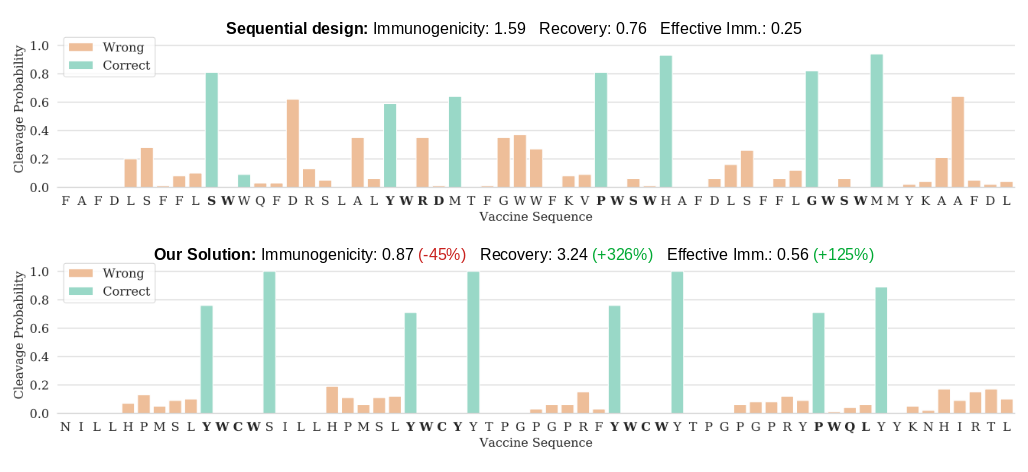

In the figure below, you see a vaccine designed sequentially with state-of-the-art tools on the top, namely OptiTope3 for epitope selection and OptiVac4 for epitope assembly, and, on the bottom, a vaccine designed with our framework. The charts show the cleavage probability for each position in the vaccine, as estimated by the simulations. The spacer sequences are highlighted in bold, and the color of the bar indicates whether cleavage in a certain position is good (green) or bad (orange).

As you can see, the vaccine designed with our solution presents larger cleavage probabilities between spacers and epitopes (the green bars), and smaller cleavage probability inside the epitopes and spacers (orange bars). The immunogenicity reported in the title is the sum of the immunogenicities of the epitopes. It is much lower for our vaccine, because we had to select epitopes that have low cleavage probability in the middle. This is something we cannot influence with the spacers, according to our cleavage model, therefore we have a limited choice of epitopes that we can use in the vaccine. However, the fact that we select epitopes based on their probability of not being cut in the middle is one of the strengths our approach, something which is not possible with current methods, and, I cannot stress it enough, the main benefit of our approach.

The second number reported in the title is the expected number of epitopes recovered correctly after proteasomal cleavage. On average, less than one epitope is recovered for the sequential design, while our simultaneous approach raises this number to more than three. It should be clear now that this increase is possible because we selected epitopes that are not as likely to be cut in the middle.

The last number is the effective immunogenicity, which is simply the average immunogenicity of the epitopes weighted by their recovery probability. Even though the individual epitopes selected by our framework are not as immunogenic, they have a greater overall effect simply by being recovered more frequently. According to this metric, the vaccines designed by our simultaneous approach are twice as effective as vaccines designed with the sequential approach.

In the paper we go deeper and analyze these metrics, as well as coverage of antigens and patients, varying the “harshness” of the proteasome, i.e. how eager it is to cleave proteins. We also study which thresholds are best in which situation, and which spacers are frequently produced by our framework. We also use a different, more advanced, cleavage prediction tool, to validate our results.

References

-

Peters, B., Nielsen, M. & Sette, A. T Cell Epitope Predictions. Annual Review of Immunology 38, (2020). ↩

-

Dönnes, P. & Kohlbacher, O. Integrated modeling of the major events in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Protein Science 14, 2132–2140 (2005). ↩

-

Toussaint, N. C., Dönnes, P. & Kohlbacher, O. A Mathematical Framework for the Selection of an Optimal Set of Peptides for Epitope-Based Vaccines. PLoS Computational Biology 4, e1000246 (2008). ↩

-

Schubert, B. & Kohlbacher, O. Designing string-of-beads vaccines with optimal spacers. Genome Medicine 8, (2016). ↩